I’m pretty sure I know where the name “Giant” came from. This is the first thought that pops into my head as I drive up to the gates of Giant’s factory in Taichung. The complex is immense — it’s that big that it has its own water tower, which has been freshly painted with bright blue racing strips and the Giant logo.

Giant is one of the main players when it comes to producing bikes, not just under its own brand name but for many of the other major bike brands as well. Giant can currently call itself the number-one producer in the bike assembly world and standing outside the gates of their Taichung factory it’s hard to see how any other manufacture could compete against this. The factory is the size of a village.

The visionary behind the brand is Mr King Liu who, back in 1972, started producing steel frames for the Taiwanese market. Unfortunately King Liu wasn’t in on the day I visited — he’d just finished a 12-day cycling tour of Taiwan despite being over 80 years old. His face was still one of the first things I spotted as I walked into Giant’s head office though, situated in a seven-story building on site.

A brief history

Giant is one of the major players in carbon production today and the company’s plant in Taichung, known as the C-Tech factory, is state of the art. History shows that Giant was beaten to the market by American firm Kestrel when it came to the first fully carbon frame, but in 1987 Giant were the first company to market with a mass production carbon frameset: the Cadex 980 C.

Come the following year and Giant spread its wings. The first order of frames for Europe came from the Netherlands. With a rapid expansion new facilities were soon needed and in 1992 Giant opened up its first Chinese base. Today Giant owns and operates a total of six factories in China and nine worldwide.

It wasn’t until 1997 that Giant eventually moved into sponsoring a big-name cycling team in the form of Manolo Saiz’s Spanish super-squad ONCE. The sight of the team’s bright yellow (or pink when competing in the Tour de France) kit is a sight from the late ’90s that many cycling fans will remember.

The team rode a controversial (if you worked at the UCI at least) and ground-breaking bike: the TCR. At that stage the pro-issue bikes were still made of alloy and it wouldn’t be until 2003 that the TCR was produced in carbon. Later incarnations of the frame, the TCR Advanced, would carry T-Mobile riders to victory after Giant managed to lure Walter Godefroot’s German team away from Pinarello.

Since then Giant has sponsored several major teams including HTC-Highroad, Rabobank through to Blanco and now the Giant-Alpecin squad.

Brandon Chou, my guide for the afternoon, told me that the compact road design was developed by Mike Burrows, the designer behind the bike ridden by Chris Boardman on his way to winning the 4000m pursuit at the 1992 Barcelona Olympics. Giant then employed Burrows to develop an all-new road bike design, influenced by MTB frame design.

“We were surprised to find out that a compact road design provided several advantages,” Brandon told me. “It was lighter, stiffer and even faster [when compared with] traditional frames.”

Further expansions

In 2008 Giant created its women’s-only brand Liv and the company also has its Momentum line, a separate brand catering to the town bike market which, I’ve been told, is a hit in China.

A sub-division of the Momentum line is YouBike. These bikes are for the bike share schemes in Taipei, Taichung and Changhua. Giant designed and built 10,000 of these bright orange bikes which are easy to spot in a city filled with scooters that the locals dash about on. I’m told Giant were also consulting partners with London’s “Boris Bikes” bike share scheme.

Giant’s design and marketing is taken care of out of an office in California which makes sense when you realise 25% of Giant’s market is in the US. Unsurprisingly China is the company’s largest market with 28% of its products sold there, while Australia accounts for 7%. The remaining 40% is spread throughout Europe and the rest of the world. Worldwide, Giant has no fewer than 11,125 dealers and the company’s annual turnover for 2013 was a staggering US$1.8 billion.

Into the factory

I’m guided out of the office and across the parking lot where Brandon waves to two security guards. They let us pass into the entrance and the factory’s main loading area. While walking past racks upon racks of carbon and alloy frames Brandon points out that he’ll let me know where I can take pictures. A lot of the areas here are off-limits — the processes they have in place are to be kept confidential.

The sheer scale of the place is something that, even wandering around, you can’t quite grasp. The whole plant covers 67,000 square meters — about the same amount of space as nine football pitches. Obviously one of my first questions is: how many bikes are produced here in a year? So far I’ve passed more racks of bikes than I’ll likely see in the rest of my lifetime.

The answer is a staggering one million a year, or 6.3 million across all of Giant’s nine factories worldwide. It makes me think that the popular Katie Melua song with the line “There are 9 million bicycles in Beijing” mightn’t be too far off the mark. Apparently one million Giant ATX bikes were sold last year alone.

Here in the Taiwan factory they produce frames not just under the Giant name but under many other brand names as well. While wandering around I eagerly spot several top-tier brands — brands from Italy, America and Switzerland are sat alongside Giant Propels and TCR framesets, all having rolled off the same production line.

The factory in Taichung is where Giant produces its high-end carbon frames. In China they have a second factory that makes the more affordable frames. With the number of Propels lined up on the steel racks here it slightly blunts the feeling of exclusivity you get when looking at one solitary Propel in your local bike shop.

Giant is able to churn out 500 carbon bikes a day, 70% of which are Giant’s own designs: Propels, TCRs and the company’s top-end mountain bike, the Anthem Advanced. The remaining 30% of frames they make are for their customers; the international players. This is only 10% of the whole factory’s output — a total of 3,500 bikes are made here daily.

Carbon sheeting

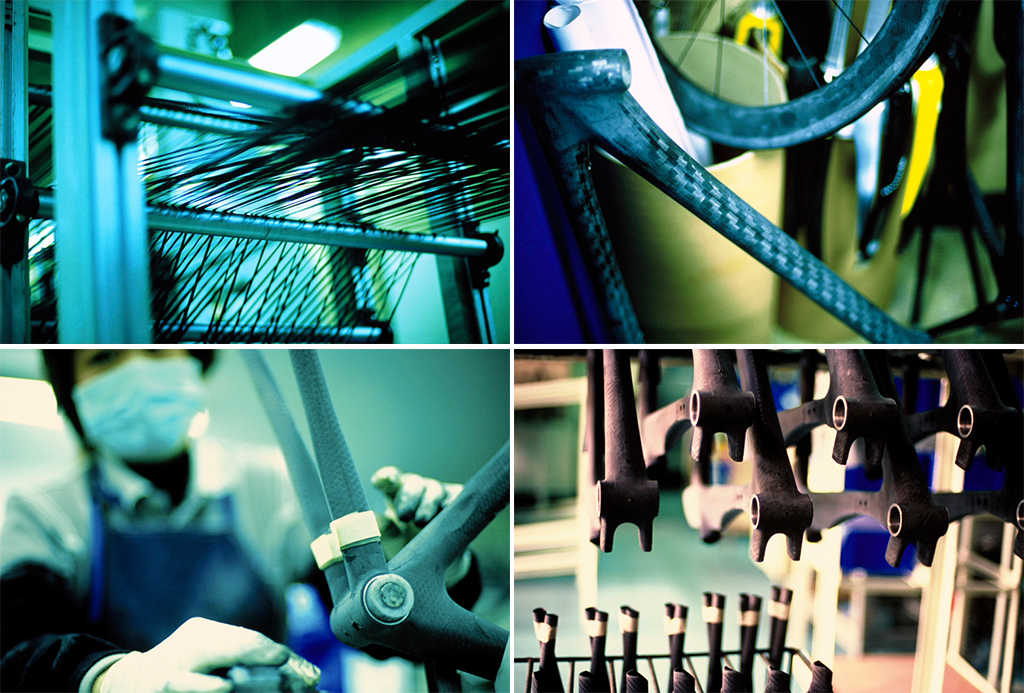

Like with my SRAM factory visit there are areas of the Giant factory that are off-limits to the visiting press. The main area is where they produce the rolls of carbon sheeting. Behind closed doors threads that are not produced by Giant are weaved together (see image below). These are then pre-impregnated with Giant’s own resin formula.

Giant wouldn’t reveal whether the company’s procedure for making carbon sheeting is any different from any other brand, but the fact that so many large and prestigious brands choose to go with Giant as their production partner must mean they are doing something right.

The only secret Brandon let me in on is the fact it’s not the carbon sheeting they like to keep quiet but rather it’s the make-up of their resin. Giant developed the resin with a chemicals partner that they have to keep secret for fear of other brands partnering with said company. It’s all very hush hush.

I’m told that each roll of carbon that Giant produces has a shelf-life of one month. If it isn’t used in this time it’s scrapped. Like any carbon it needs to be kept cold for best performance and the freezer here chills the carbon to -20 degrees Celsius. Before production the carbon needs eight hours to thaw before being sent for hand cutting.

My tour of the carbon facility is pretty limited; instead I’m shown how they turn this carbon sheeting into the frames and components we all recognise.

Image: supplied by Giant.

Building a frame

Through a large window I peer at multiple rows of women all decked out in clothing more suited to an operating theatre than a bike factory. They each sit concentrating on small sections of what will eventually turn out to be a frameset. It’s pointed out to me that this work is intricate and that they find women best suited to this work.

I’m told that they’ve found that women tend to be more patient and can focus on a singular job better than the guys. It’s a recurring theme that I’ve seen at many factories. Blokes apparently aren’t patient enough — we let our brains wander and our big, cumbersome hands tend to fumble. (The paint shop is another domain where you’ll only see women.)

In front of each of the workers sits a tray with small sheets of carbon cut out into different shapes. Each of these shapes must be placed in a correct order and in the exact spot they are needed. It’s a process that takes the staff up to three months to learn. Lay a sheet a few millimetres in the wrong direction or in the incorrect order and the characteristics and integrity of the frame may be compromised.

Image: supplied by Giant

Each tray holds numerous pieces of carbon. Once these pieces have been placed and smoothed out with the aid of a hot air gun, they are racked up for the next person to apply their eight sheets of carbon. Between six and eight trays are needed for each frame.

Industrial sized hair dryers are used to soften up the carbon layers to lay them smoothly on to the previous layer and to allow the resin to become tacky enough to attach the next piece. The shaping of the tubes is formed over plastic rods with a plastic bag between the tube and the first carbon layer. This bag is left in place for the next step in the moulding process.

As many as 300,000 pieces of carbon can be used in any one day with each frame taking anywhere between 300 and 400 individual pieces. One frame takes a total of 18 hours to produce and goes through 32 different pairs of hands before it’s ready to leave for painting. In this time it’ll undergo 14 quality checks.

One item that is checked particularly rigorously is forks. I’m told that every fork must be made to 100% perfection. On a frame small wrinkles in carbon layup can be doctored but with a fork every piece must reach an extremely high standard. If even the slightest defect is observed in an X-ray machine then the fork is discarded.

Of the 2,000 staff here it’s the old pros of the factory that get to make the real cool stuff. Only the staff who have been at Giant long enough to acquire the skills are allowed to build the top-end Propels.

Giant seems to like having women work on the more details-focused aspects of bike creation and assembly.

The climate-controlled room where the lay-up process happens is situated within one of the main factory units, yet it’s like its own self-contained environment. Everything is monitored: humidity, air pressure, temperature, air flow and the particles floating in the air. A computer monitors all of this 24 hours a day, seven days a week. Alarms sound if problems arise.

All around the oasis that is the calm carbon lay-up rooms people are busying themselves on machines that have clearly been churning out bike parts in staggering numbers for years and years. The paint on the machines has been worn away and replaced with a layer of factory dust.

It’s here that the moulding takes place. The carbon pieces are precisely placed into steel moulds and then clamped with the secondary top mould. Each mould is a CNC-machined steel plate for a different piece of the bike, from the seatstays through to the bottom bracket. Each of these moulds is for a single size of bike. These are then placed into an oven where they are baked while 16kg per square cm of pressure is forced into the plastic bags to inflate the carbon and force it in to the mould’s shape.

Image: supplied by Giant.

Piecing it all together

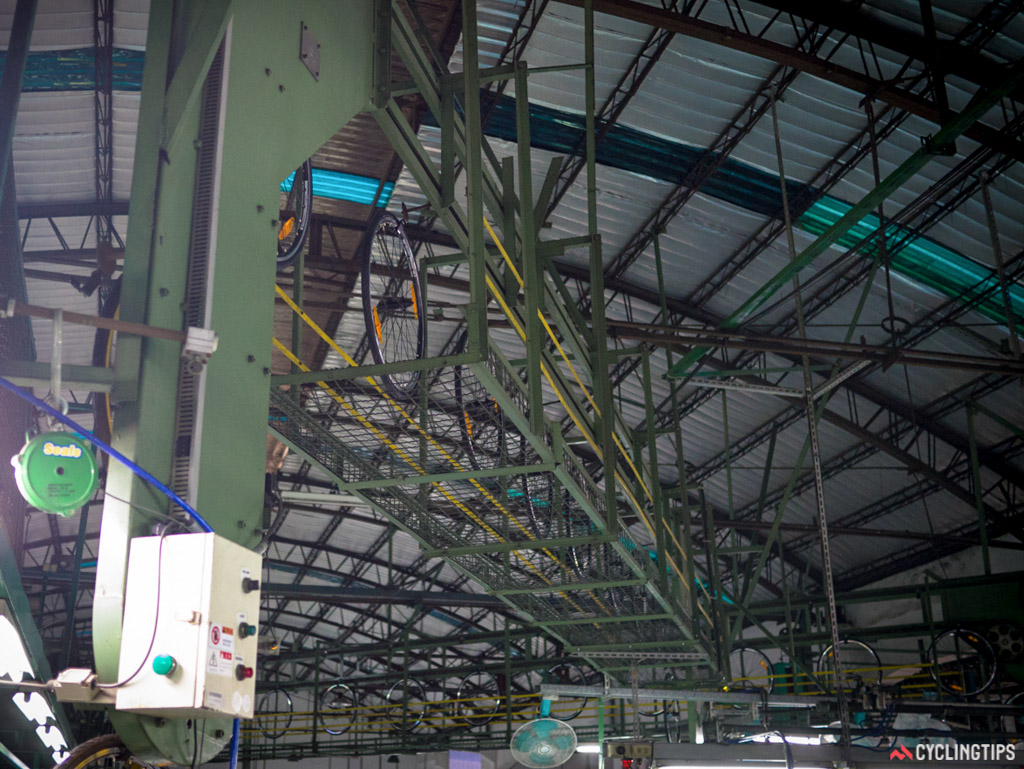

The assembly line for Giant’s alloy frames looks just like a car production plant but on a smaller scale. A long conveyor belt slowly slides the frames along to different members of staff who mount a single part, be it a rear mech hanger or a stem. This is all timed to perfection — a calculated 37 seconds is allowed for each job.

At one section of the main assembly conveyor belt wheels slowly descend from above off yet another conveyor belt that looks like it runs from a separate part of the factory. It strikes me that there are whole areas of the factory I’ve not seen yet, where people are rapidly putting tyres and tubes on to these wheels, probably within 37 seconds as well.

The whole unit I’m in has bikes hanging in the air in various states of completion, all of them swinging this way and that. At the end of the conveyor belt a bike is placed in a cardboard box, again in 37 seconds, and sent off up a steep ramp to a warehouse.

The warehousing is monstrous but it too is off limits with the camera. I stand there trying to count the pallets of bikes. I work out that each pallet holds six bikes and that the single section I manage to take in before I’m whisked away is 15 pallets long by 10 pallets high. How deep it goes I’ll never find out.

Trucks wait with their containers slowly being crammed full of new bikes.

A wheel is dropped from a conveyor belt overhead into the assembly line.

I drove away from Giant’s Taichung factory with many thoughts about my visit, not least just how impressive and streamlined frame production can be. Giant has more than 42 years of experience and history behind it, and the company is a market leader at least in part because of the efficiency it has in place here and at its other facilities.

Sure, it might not be driven by the same sort of passion you’d find from a small bespoke brand but the passion is definitely present. It’s just hidden away behind the sound of heavy machinery and multiple lorries taking shiny new bikes to millions of happy new owners.

Photo gallery

Each step of the assembly process is carefully timed and controlled.

Handlebars ready for the assembly line.

Wheels arrive on the factory floor from somewhere else in the vast complex.

Attaching a rear mech in the factory.

Shipped and ready to go.