Mauna Kea is different things to different people. To ancient Hawaiians it’s a sacred site, the summit of which was off limits to all but the highest-ranking of tribal chiefs. To astronomers, it’s one of Earth’s greatest vantage points (due to high altitude and dry air, among other factors) and the site of no fewer than 13 telescopes. To cyclists it’s one of the most challenging cycling climbs on the planet … at least to those that know about it.

I arrived in Hilo on the Thursday night after 25 hours of travel from Oslo and assembled my bike in the hotel before going to bed. With an 11-hour time difference between Hawaii and Norway I didn’t get much sleep and at 5am I suited up and headed over to Ken’s House of Pancakes for breakfast and to meet-up with local photographer Jonathan Rawle.

I had made contact with Jonathan before leaving Norway and he was to follow me up in a 4×4 truck - both for support and to take pictures. Jonathan didn’t have jet lag, so it was an early breakfast for him. Luckily for me Ken’s serves coffee by the pot, not the cup.

In the past decade I’ve cycled up numerous mountains in Europe, but this was the first time I’d started a climb from the ocean. As we made our final preparations by the sea-front I could see the summit of Mauna Kea off in the distance, just as a full moon was setting behind the observatories at the top. It looked a long way away to the naked eye, and having just checked the weather forecast I knew that the temperature at the summit was -4 degrees celsius. Very high, very cold, and seemingly very far away. A stark contrast to the weather around us in Hilo.

To provide some context, the Mauna Kea climb has four times the altitude gain of the famous Alpe d’Huez. Throw in a 7km gravel section at the top — à la Colle de Finestre — and mix in some sections where gradients are on par with Monte Zoncolan — and you have what is arguably the world’s hardest cycling climb.

I had checked Strava to see who had done the climb before me and was a bit surprised to see only 17 cyclists on the list. Reading through the comments from those that had done the climb I learned that most riders used a two-bike strategy: a road bike for the paved sections (90% of the climb) and a mountain bike for the 7km gravel section in the latter part of the ascent (and probably also for the easier gearing). Using two bikes isn’t exactly cheating, but there’s something nicer about doing it all on the same bike, which I was determined to do.

I was borrowing a new Specialized Diverge, a gravel-grinder with compact crankset and 32-tooth cassette, 32mm slicks and hydraulic disc brakes. I don’t think I used the brakes once … but I sure did get to use the lowest gear!

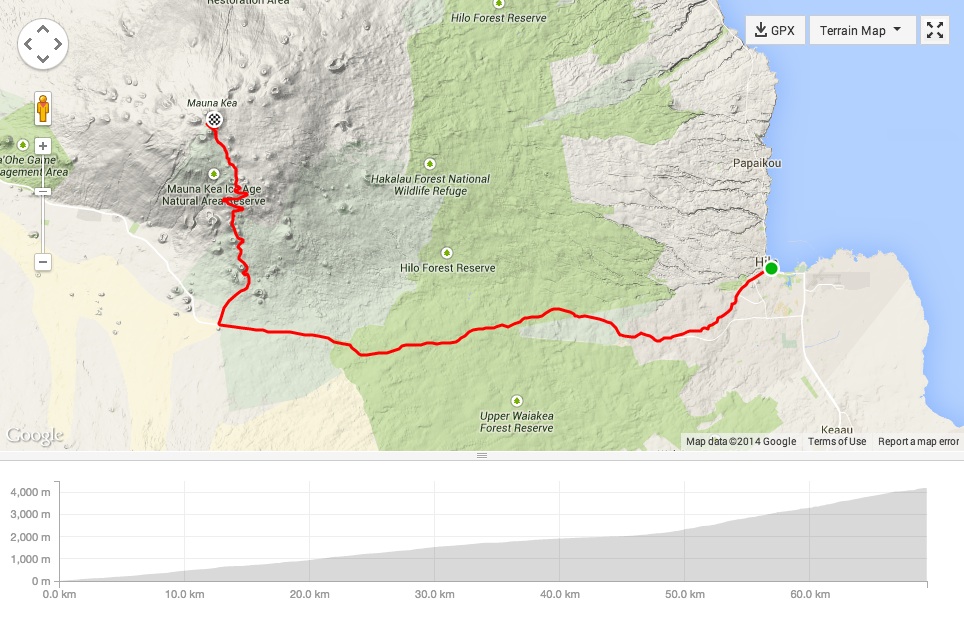

Climbing Mauna Kea isn’t really about trying to ride quickly to the top. It’s more a matter of just trying to get there (as I was soon about to experience). The full, 65km+(!) climb from Hilo to Mauna Kea can be divided roughly into two main sections: the ride out of Hilo and into the centre of the Island along the highway Saddle Road (first 2,000 meters of ascent), and then the Mauna Kea Access Road which goes from the highway up to the observatories (last 2,200 meters of ascent).

The first section is 44km long with a steady, 5% average gradient, while the second part is 22km with a large variety of gradients (up to 20% some places) that average out at 10%, and including a 7km gravel section. Briefly summarised: the first part is manageable; the second part is hell.

The ride out of Hilo and up the highway ticked by without too much trouble. With a steady 5% gradient and excellent asphalt I got lured into a false sense of accomplishment. I got to thinking “this climb is easier than I expected!”, even with a slight headwind.

Being mostly highway I was thankful for the large shoulder on the road to cycle on. Saddle Road is the main connection between the eastern and western sides of the island, and although traffic isn’t too plentiful many drive fast so it’s safest to be tucked well to the side of the road. The whole way in to the centre of the island I could see the peak of Mauna Kea to my right getting gradually closer.

With roughly 2,000m of climbing done I turned to the right, joining the Mauna Kea Access Road and soon hit one of the steepest sections of the day — a 2km stretch with over 13% average — before arriving at the Mauna Kea Visitor Information Station.

The Visitor Information Station is actually the only place on the entire climb where it is possible to refill one’s water bottles. For this reason it’s a tough climb to do without a support vehicle (at least not without carrying a sizeable backpack with water, food and clothes). Due to the danger of altitude sickness and the possibility of rapidly changing weather (including strong winds, rain and even snow) I definitely would not recommend attempting this climb without support.

All visitors are encouraged to stop for a minimum of 30 minutes at the Visitor Information Station to help acclimatise to the high altitude. That recommendation is not that important when cycling as the ascent is significantly slower than when driving a car, at least for me! After a quick water refill from the truck I pushed on.

Shortly after the Information Station the gravel section starts. Welcome to hell! Mauna Kea is a volcano, and the gravel here is different from normal gravel. It consists of rocks mixed with dry and dusty volcanic ash which doesn’t “pack” despite a lot of rain. The result is a gravel road that’s more like sand, making it extremely hard to get traction on a bicycle.

At the start of the gravel there is a huge sign stating “only 4×4 vehicles”. Well a bicycle only has two, so I didn’t really have any choice. I quickly realised that standing up was not an option any more. Gradients undulated between 5% and 15%, and trying to maintain an adequate cadence with the 34-32 gear ratio while keeping the 32mm slicks from spinning was extremely hard. Simply put: I should have had even lower gears (perhaps by installing an MTB crank-set), and a thicker rear tire with knobbies (the Diverge supports up to 35mm, which I should have put on).

Luckily I had chosen MTB pedals and shoes, as there were some short parts where I simply had no other choice but to walk. These were typically sharp turns with 13-15% gradients where cars/trucks had made the gravel even looser than normal.

The 7km-long gravel section ends at 3,600 meters above sea level. It’s hard to describe how exhausted I was feeling at this point. It was probably a combination of several factors: the low oxygen levels, perhaps not enough to drink/eat, and just general exhaustion from having done more than 60km of climbing.

From here to the summit it’s only 5.8km. It took me an hour and 20 minutes, including several short breaks to catch my breath (literally). It’s literally the slowest 5.8km I have ever ridden in my life.

Jonathan and his photo-assistant Chris were cheering me on and supplying me with water/food — I don’t know if I would have made it up without them. At one point I suddenly lost my bike-handling skills (I think I was fainting) and almost cycled into a ditch before swinging back onto the road. I managed to jump off and collapse on the ground in the middle of the road.

Dizzy and nauseous, but after getting some oxygen back into my system together with a bite to eat and some water, I quickly felt a bit better again. Luckily the weather had stayed sunny, despite forecasts predicting fog and rain, so at least I didn’t have to deal with being cold.

I got a second wind in the last kilometre before the summit, mostly because I realised that I would make it! The extra adrenaline also gave me the strength to appreciate the scenery.

I’ve cycled many a mountain where the views from the summit are actually a disappointment, but in stark contrast to these, Mauna Kea delivers perhaps the most amazing view I’ve ever seen. A 360-degree view which, coupled with the many telescope observatories, resembles something out of a sci-fi movie. It’s like standing on the moon but looking down at Earth through the clouds.

To the south the view includes the island’s second highest mountain, Mauna Loa (4,169m), and to the north, the mountain Haleakala (3,055m) on the neighbouring island of Maui. It’s simply a unique summit with a breathtaking view — a fitting reward for anyone who cycles up to the top. Those tourists in their trucks cannot possibly appreciate it as much!

While walking around enjoying the view, I could definitely notice the lack of oxygen. Given I was still feeling nauseous (altitude sickness?) I decided not to cycle down again as planned and instead hitched a ride with Jonathan and Chris.

On return to the hotel I noticed that one of the water bottles I had finished off at the summit looked as if it had been run over by a truck due to the compression of air inside during the drive down! A reminder of the extreme difference in altitude and air-pressure from top to bottom.

I flew back to Norway the day after the ride, prompting many people back home to say: “You flew to the other side of the world to cycle one hill and then flew back again?! Ok, you’ve lost it pal!” The truth is it was worth it by a long shot. If there is one “hill” that can justify international travel to climb, then Mauna Kea is it.

Mauna Kea is the mother of all monster-climbs and should be noted on every serious cyclist’s bucket list. Just make sure you remember sunscreen though. I didn’t, and I got scorched!