Shayne Bannan has been the driving force between the development of many of the support services Australia’s European-based cyclists now take for granted. But Shayne is humble about that statement. He said, “It’s not about the Shayne Bannan story, there’s been a lot of people over many years who have contributed into the dream.”

“It’s been an increadible journey. I obviously speak quite a lot with Gerry Ryan who attributes his success in business on the people who he puts around him. That can be said about professional cycling too.”

As Shayne told us, it was in the 1980s that things started to gain momentum.

“Charlie Walsh gave me my first opportunity into coaching back in 1987 as a scholarship coach with the Australian Insitute of Sport (AIS). That’s when I first started bringing teams overseas. My first team was the women’s team — I was the national women’s coach.Our first race was the women’s Tour de France. Back in those days it was held in conjunction with the last 12 days of the men’s Tour de France. That was a great experience.”

But in those early days, conditions were far from ideal for the riders and for those supporting the riders:

“We often talk about the story where myself and Jacques, a mechanic in that period, rented a three-bedroom house in Cantagrillo, Italy. The riders would sleep in the bedrooms and Jacques and I would sleep on the first and second landing of the staircase. Every morning we’d pack up our beds and get brekkie ready.

You just didn’t think anything of it. It was new, it was exciting, and was really fun times when I look back at it.”

But despite being enjoyable and memorable, sleeping on the floor or renting hotels from race to race wasn’t sustainable – Australian cycling needed a proper base in Europe.

In 1998 the Australian U23 road cycling program had a small base near Pistoia in Tuscany. In the following years that base was moved to a big farmhouse in the the Reggo Emelia region but things were only just getting started.

At some point in 2004 Shayne Bannan had the then-director of the AIS, Michael Scott, over for dinner. Michael asked Shayne what was needed to take things to the next level.

“I said that the fundamental issue we have is the servicing of athletes to a standard that we have at the AIS”, Shayne said. “’What we need is a mini-AIS in Europe’,” Shayne told Michael.

Shayne envisaged a centre where Australian athletes – not just cyclists – could come for anywhere between a week and six weeks and have access to recovery, gyms, physiotherapy and everything they might have back at the AIS in Canberra.

“I could see Michael thinking about it and the next morning I had to drive him to the airport. He didn’t say that much and I though ‘Geez, he must think I was a bloody idiot with me going on about this stuff last night’.

I dropped him off at the airport and as he left he said, ‘I had a think about what we discussed last night and I reckon it’s a good idea. I’ll put the business plan together and put it to the sports commission, you find the facility.'”

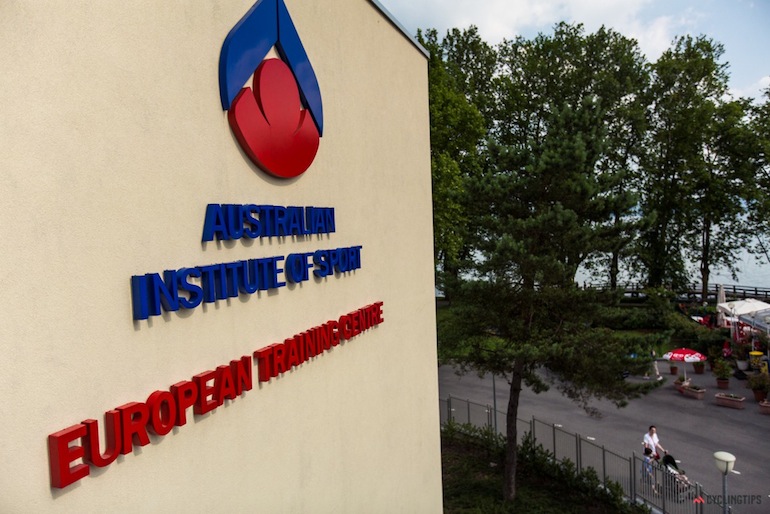

After dropping Michael at the airport Shayne got on the phone to legendary cycling coach Aldo Sassi, to get his advice on where a European mini-AIS could be set up. An hour later Aldo and Shayne organised to meet at the Mapei Sports Centre in Varese –- one of the most respected sports centres in Europe — and the pair drove down to the shores of Lake Varese where a derelict old school building stood.

As Shayne recalls: “Aldo and I got out of the car and I immediately said ‘that’s it, that’s the ETC’. I rang Michael Scott straight away and said, ‘I’ve found it. Now you go find us the money!'”

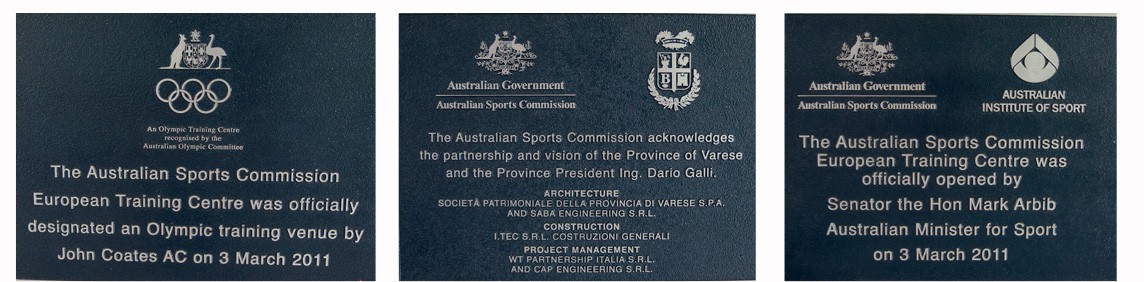

After two years of report-writing and analysis, not to mention discussions with the provincial government of Varese, the Australian Sports Commission and administrators of other sports, Shayne and his team finally got the go-ahead. It took until March 2011 for the centre to be open.

While the AIS ETC was founded largely to support Australian cyclists and rowers (who use Lake Varese, right on the centre’s doorstep) the ETC is now used by Australian athletes in all manner of sports, including golf, boxing, walking, sailing, basketball and wheelchair basketball.

Many of Australia’s representatives at the London 2012 Olympics used the ETC for many weeks in the lead up to the Games, to acclimatise to conditions in Europe and to get in some last minute training.

The ETC houses a sports lab, a massage room, medical consulting rooms, performance analysis rooms, lecture halls, gyms, temporary offices (for athletes who are also students, for example), recovery pools, dining areas, accommodation for up to 50 athletes and more.

In addition to the facilities on offer it’s the little touches that help to make the place feel like a little piece of Australia on the other side of the world. For example, every day the staff print off copies of the major Australian newspapers so the athletes can feel like they’re connected with their life back home.

The place is beautifully laid out with plenty of natural light and walking around the facility we couldn’t help but wish we were professional athletes spending some time there.

While the AIS ETC is a home away from home for Australian athletes of all varieties, Australian cycling has another home nearby in Castronno, just up the road from the ETC.

The residential building, which contains 12 apartments, was built in 2005 and is now home to several members of the Australian cycling family. Several riders on the Orica-AIS women’s team call the Castronno base home, as do members of administration staff, team directors, and the Australian U23 men’s team.

The U23s spend six months of the year at the base — March to September — living and training in Castronno, drawing on the support of the Australian cycling family in the area and immersing themselves in life as a pro cyclist.

While visiting the Castronno base we bumped into Australian U23 rider Adam Phelan, who rides for Drapac Professional Cycling while back home in Australia. Behind Phelan is the house where the U23’s and Women’s teams call home away from home.

In many ways, the establishment of the ETC and the Castronno base were stepping stones on the path to creating Australia’s first WorldTour team: Orica-GreenEDGE. As Shayne Bannan told us:

“I’ve always been a big believer in processes and natural progression. The discussions we had in the ’80s and ’90s were about building the blocks and setting up the state institutes and acadamies, getting the programs based in Europe, having the screening camps and so on.

We were building the foundations and knowing that the way we’re … doing this to get results at Olympics and World Championships and to eventually get our own WorldTour team.”

While the riders on the Orica-GreenEDGE roster live in cities all around Europe (and beyond) the team’s service course is based in Varese. (Despite being an Australian team, it would make no sense to have the Orica-GreenEDGE service course in Australia — the vast majority of Orica-GreenEDGE’s races are held in Europe.)

This facility is home to Orica-GreenEDGE’s fleet of vehicles, storage for the multitude of equipment required by a WorldTour team (and for the Orica-AIS, U23 and Australian track teams), offices for team management, and more. (If you haven’t already, check out our piece about the Orica-GreenEDGE service course which includes a whole bunch of photos.)

While it took until 2012 for Orica-GreenEDGE to ride in its first race as a WorldTour team, the wheels had been in motion long before that.

“I think it was in a lot of people’s minds”, Shayne said, “but we really started to talk about it in ’97 or ’98 when we started having screening camps.”

At that time there were only roughly a dozen Australians riding at the highest level of the sport, including Stuart O’Grady, Robbie McEwan, Henk Vogels and Dave McKenzie. Three times a year the riders were brought into screening caps in Europe to be looked after by physiotherapists and other support staff in order to “get them back on the right track”. As Shayne told us:

“It was really appreciated by the guys who came in. At the end of these camps we’d always have a barby and we’d sit around talking and dreaming about having an Australian pro team one day.”

Now that the dream is a reality and the team is in its second season and very much competing at the highest level, Shayne Bannan is focused on the future of Orica-GreenEDGE – a future that he hopes will last for 15 or 20 years. And as with much of what Shane has done for cycling in the past couple decades, he’s focused squarely on providing support for those that need it:

“To really strive as being recognised as a world leader in servicing athletes is what we’re about and on the road to achieve. Doing that is a natural progression to getting results.”

But, as Shayne admits, it’s an ongoing process: “In elite sport there is no finish line, is there?”

Having spent several days touring the AIS ETC, the Castronno base and the Orica-GreenEDGE service course, and speaking to many people involved, it’s clear there’s a great family feel to these facilities and operations.

Despite being many thousands of kilometres away from home, Australian cycling really does have a home in Italy. We can only hope this continues to be the case and that Australian riders keep getting the support they need while abroad, to help them mix it with the world’s best.

- The gym at the AIS’s European Training Centre.

- The ETC has a wonderful open feel to it with plenty of natural light.

- The basement gym/storage room at the Castronno base. Shara Gillow (the reigning Australian time trial champion) was on the trainer while we were taking a tour.

- We were given a tour of the Castronno base by U23 coach James Victor.

- On our second day in Varese we were lucky enough to go for a ride with two Orica-AIS riders who live locally: Jessie MacLean (left in both images) and Gracie Elvin (reigning national road race champion.)